Bladder Cancer Treatment: Treatment - Patient Information [NCI]

This information is produced and provided by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The information in this topic may have changed since it was written. For the most current information, contact the National Cancer Institute via the Internet web site at http://cancer.gov or call 1-800-4-CANCER.

What Is Bladder Cancer?

Bladder cancer occurs when cells in the bladder start to grow without control. The bladder is a hollow, balloon-shaped organ in the lower part of the abdomen that stores urine.

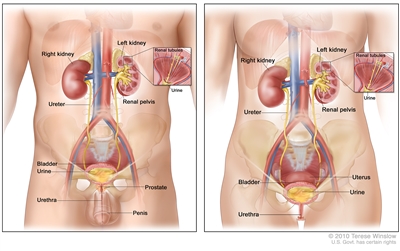

The bladder has a muscular wall that allows it to get larger to store urine made by the kidneys and to shrink to squeeze urine out of the body. There are two kidneys, one on each side of the backbone, above the waist. The bladder and kidneys work together to remove toxins and wastes from your body through urine:

- Tiny tubules in the kidneys filter and clean the blood.

- These tubules take out waste products and make urine.

- The urine passes from each kidney through a long tube called a ureter into the bladder.

- The bladder holds the urine until it passes through a tube called the urethra and leaves the body.

Anatomy of the male urinary system (left panel) and female urinary system (right panel) showing the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra. The inside of the left kidney shows the renal pelvis. An inset shows the renal tubules and urine. Also shown are the prostate and penis (left panel) and the uterus (right panel). Urine is made in the renal tubules and collects in the renal pelvis of each kidney. The urine flows from the kidneys through the ureters to the bladder. The urine is stored in the bladder until it leaves the body through the urethra.

Types of bladder cancer

Urothelial carcinoma (also called transitional cell carcinoma) is cancer that begins in the urothelial cells, which line the urethra, bladder, ureters, renal pelvis, and some other organs. Almost all bladder cancers are urothelial carcinomas.

Urothelial cells are also called transitional cells because they change shape. These cells are able to stretch when the bladder is full of urine and shrink when it is emptied.

Other types of bladder cancer are rare:

- Squamous cell carcinoma is cancer that begins in squamous cells (thin, flat cells lining the inside of the bladder). This type of cancer may form after long-term irritation or infection with a tropical parasite called schistosomiasis, which is common in Africa and the Middle East but rare in the United States. When chronic irritation occurs, transitional cells that line the bladder can gradually change to squamous cells.

- Adenocarcinoma is cancer that begins in glandular cells that are found in the lining of the bladder. Glandular cells in the bladder make mucus and other substances.

- Small cell carcinoma of the bladder is cancer that begins in neuroendocrine cells (nerve-like cells that release hormones into the blood in response to a signal from the nervous system).

There are other ways to describe bladder cancer:

- Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer is cancer that has not reached the muscle wall of the bladder. Most bladder cancers are non-muscle-invasive.

- Muscle-invasive bladder cancer is cancer that has spread through the lining of the bladder and into the muscle wall of the bladder or beyond it.

Learn more about bladder cancer

Many bladder cancer symptoms are also seen with other less serious conditions. These are the warning signs you shouldn't ignore.

Using tobacco, especially smoking cigarettes, is a major risk factor for bladder cancer. Learn about tobacco use and other risk factors for bladder cancer and what you can do to lower your risk.

Learn about bladder cancer screening tests for people at high risk.

Learn about the tests that are used to diagnose and stage bladder cancer.

Learn about bladder cancer survival rates and why this statistic doesn't predict exactly what will happen to you.

Stage refers to the extent of your cancer, such as how large the tumor is and if it has spread. Learn about bladder cancer stages, an important factor in deciding your treatment plan.

Learn about the different ways bladder cancer can be treated.

Coping with bladder cancer and the side effects of treatment can feel overwhelming. Learn about resources to help you cope and gain a sense of control.

Childhood bladder cancer is a very rare type of cancer that forms in the tissues of the bladder. Learn about the symptoms of bladder cancer in children, and how it is diagnosed and treated.

Bladder Cancer Causes and Risk Factors

Bladder cancer is caused by certain changes in how bladder cells function, especially how they grow and divide into new cells. There are many risk factors for bladder cancer, but many do not directly cause cancer. Instead, they increase the chance of DNA damage in cells that may lead to bladder cancer. To learn more about how cancer develops, see What Is Cancer?

A risk factor is anything that increases the chance of getting a disease. Some risk factors for bladder cancer, like using tobacco, can be changed. Risk factors also include things people cannot change, like their age and family history. It's important to learn about risk factors for bladder cancer because it can help you make choices that might lower your risk of getting it.

Risk factors for bladder cancer

In the United States, bladder cancer occurs more often in men than in women, and more often in White individuals than in Black individuals. Bladder cancer can be diagnosed at any age, but the risk increases as a person gets older.

Using tobacco, especially smoking cigarettes, is a major risk factor for bladder cancer. Tobacco contains harmful chemicals called carcinogens. When you use tobacco, these chemicals get absorbed into the bloodstream, are filtered by the kidneys, and then collect in the urine. This exposes your bladder to high levels of these chemicals, which can damage the DNA in the cells lining your bladder. Learn about different tools to help you quit smoking and how to use them.

Other risk factors for bladder cancer include

- having a family history of bladder cancer

- having certain changes in the genes that are linked to bladder cancer, such as HRAS, RB1, PTEN /MMAC1, NAT2, and GSTM1

- being exposed to paints, dyes, metals, or petroleum products in the workplace

- past treatment with radiation therapy to the pelvis or with certain anticancer drugs, such as cyclophosphamide or ifosfamide

- taking the Chinese herb Aristolochia fangchi

- drinking water from a well that has high levels of arsenic

- drinking water that has been treated with chlorine

- having a bladder infection caused by a parasite called Schistosoma haematobium, which is common in Africa and the Middle East but rare in the United States

- using urinary catheters for a long time

Having one or more of these risk factors does not necessarily mean you will get bladder cancer. Many people with risk factors never develop bladder cancer, while others with no known risk factors do. Talk with your doctor if you think you might be at risk of bladder cancer. Bladder cancer screening options may be available to you.

Bladder Cancer Symptoms

The symptoms of bladder cancer can vary from person to person. The most common symptom is blood in the urine, called hematuria. It's often slightly rusty to bright red in color. You may see blood in your urine at one point, then not see it again for a while. Sometimes there are very small amounts of blood in the urine that can only be found by having a test done.

Other common symptoms of bladder cancer include

- frequent urination

- pain or burning during urination

- feeling as if you need to urinate even if your bladder isn't full

- urinating often during the night

When the cancer has grown large or spread beyond the bladder to other parts of the body, symptoms may include

- being unable to urinate

- lower back pain on one side of the body

- pain in the abdomen

- bone pain or tenderness

- unintended weight loss and loss of appetite

- swelling in the feet

- feeling tired

It's important to check with your doctor if you have any of these symptoms. Keep in mind that urinary tract infections, kidney or bladder stones, or other problems related to the kidney could be the cause, not cancer. Your doctor will ask you when your symptoms started and how often you're having them. They will most likely ask you to give a urine sample as a first step in diagnosing what is causing your symptoms. To learn more, see Bladder Cancer Diagnosis.

Bladder Cancer Diagnosis

If you have symptoms or lab test results that suggest bladder cancer, your doctor will need to find out if they're due to cancer or another condition. Your doctor may

- ask about your personal and family medical history to learn more about your symptoms and possible risk factors for bladder cancer

- ask for a sample of your urine so it can be checked in the lab for blood, abnormal cells, or infection

- do a physical exam, which for women, may include a pelvic exam, to check for signs of cancer

Depending on your symptoms, medical history, and results of your urine lab tests and physical exam, your doctor may recommend more tests to find out if you have bladder cancer, and if so, its extent (stage).

Tests to diagnose bladder cancer

The following tests and procedures are used to diagnose bladder cancer. The results will also help you and your doctor plan treatment.

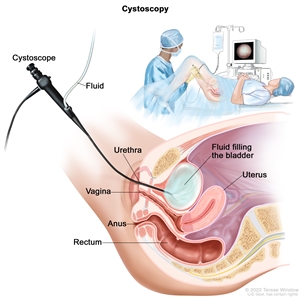

Cystoscopy

Cystoscopy is a procedure in which the doctor looks inside the bladder and urethra (the tube that carries urine out of your body) to check for abnormal areas. A cystoscope is slowly inserted through the urethra into the bladder to allow the doctor to see inside. A cystoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing. It may also have a tool to remove very small bladder tumors or tissue samples for biopsy. Cystoscopy helps to diagnose, and sometimes treat, bladder cancer and other conditions.

Cystoscopy. A cystoscope (a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing) is inserted through the urethra into the bladder. Fluid is used to fill the bladder. The doctor looks at an image of the inner wall of the bladder on a computer monitor to check for abnormal areas.

Biopsy

A biopsy is usually done during a cystoscopy procedure. Biopsy is a procedure in which a sample of cells or tissue is removed from the bladder so that a pathologist can view it under a microscope to check for signs of cancer. It may be possible to remove the entire tumor at the time of the biopsy.

Talk with your doctor to learn what to expect during and after your cystoscopy and biopsy. Some people have blood in the urine or discomfort and a burning sensation while urinating for a day or two.

To learn about the type of information that can be found in a pathologist's report about the cells or tissue removed during a biopsy, see Pathology Reports.

Computed tomography (CT) urogram or intravenous pyelogram (IVP)

CT urogram is a test that takes a CT scan of the urinary tract using a contrast dye injected into a vein. To begin the procedure, a CT machine takes a series of detailed pictures of the kidneys. The contrast dye is then injected, and another CT scan of the kidneys, bladder, and ureters is done. About 10 minutes later, a final scan is taken as the contrast dye drains from the kidneys into the bladder. CT urogram also captures detailed pictures of nearby bones, soft tissues, and blood vessels. This allows the doctor to see how well your urinary tract is working and to check for signs of disease.

IVP is an x-ray imaging test of your urinary tract. After a contrast dye is injected into a vein, a series of x-ray pictures of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder are taken to find out if cancer is present in these organs. As the contrast dye moves through the kidneys, ureters, and bladder, more x-ray pictures are taken at specific times. This allows your doctor to see how well your urinary tract is working and to check for signs of disease.

Urine tumor marker test

Urinary tumor markers are substances found in the urine that are either made by bladder cancer cells or that the body makes in response to bladder cancer. For this test, a sample of urine is checked in the lab to detect the presence of these substances. Urine tumor marker tests may be used to help diagnose some types of bladder cancer.

Tests to stage bladder cancer

If you're diagnosed with bladder cancer, you will be referred to a urologic oncologist. This is a doctor who specializes in diagnosing and treating cancers of the male and female urinary tract and the male reproductive organs. They will recommend tests to determine the extent of cancer. Sometimes the cancer is only in the bladder. Or, it may have spread from the bladder to other parts of the body. The process of learning the extent of cancer in the body is called staging. It is important to know the stage of the bladder cancer to plan treatment.

For information about a specific stage of bladder cancer, see Bladder Cancer Stages.

The following imaging tests may be used to determine the bladder cancer stage.

Computed tomography (CT) scan

A CT scan uses a computer linked to an x-ray machine to make a series of detailed x-ray pictures of areas inside the body from different angles. A dye may be injected into a vein or swallowed to help the organs or tissues show up more clearly.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI uses a magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body, such as the bladder. This procedure is also called nuclear magnetic resonance imaging. Images may be taken at three different times after the dye is injected, to get the best picture of abnormal areas in the bladder. This is called triple-phase MRI.

Chest x-ray

A chest x-ray is an x-ray of the organs and bones inside the chest. An x-ray is a type of high-energy radiation that can go through the body and onto film, making a picture of areas inside the chest.

Bone scan

A bone scan is a procedure that checks to see if there are rapidly dividing cells, such as cancer cells, in the bone. A very small amount of radioactive material is injected into a vein and travels through the bloodstream. The radioactive material collects in the bones with cancer and is detected by a scanner.

Getting a second opinion

Some people may want to get a second opinion to confirm their bladder cancer diagnosis and treatment plan. If you choose to seek a second opinion, you will need to get important medical test results and reports from the first doctor to share with the second doctor. The second doctor will review the pathology report, slides, and scans before giving a recommendation. The doctor who gives the second opinion may agree with your first doctor, suggest changes or another approach, or provide more information about your cancer.

To learn more about choosing a doctor and getting a second opinion, see Finding Cancer Care. You can contact NCI's Cancer Information Service via chat, email, or phone (both in English and Spanish) for help finding a doctor, hospital, or getting a second opinion. For questions you might want to ask at your appointments, see Questions to Ask Your Doctor.

Bladder Cancer Prognosis and Survival Rates

If you've been diagnosed with bladder cancer, you may have questions about how serious the cancer is and your chances of survival. The likely outcome or course of a disease is called prognosis.

The prognosis for bladder cancer depends on many factors:

- the stage of the cancer, including whether the cancer

- has not reached the muscle wall of the bladder (called non-muscle-invasive or superficial bladder cancer) or

- has spread through the inner lining of the bladder and into the muscle wall of the bladder or beyond it (called muscle-invasive bladder cancer or invasive bladder cancer)

- the type of bladder cancer

- whether the cancer is low grade or high grade

- the patient's age and general health

For non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer, prognosis also depends on whether

- there are many tumors or large tumors

- the cancer has grown into the connective tissue next to the lining of the bladder

- the cancer has come back after treatment

Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer can often be cured.

For muscle-invasive bladder cancer, prognosis also depends on whether carcinoma in situ is also present.

Survival rates for bladder cancer

Doctors estimate bladder cancer prognosis by using statistics collected over many years from people with bladder cancer. One statistic that is commonly used in making a prognosis is the 5-year relative survival rate. The 5-year relative survival rate tells you what percent of people with the same type and stage of bladder cancer are alive 5 years after their cancer was diagnosed, compared with people in the overall population. For example, the 5-year relative survival rate for localized bladder cancer is 71%. This means that people diagnosed with localized bladder cancer are 71% as likely as someone who does not have bladder cancer to be alive 5 years after diagnosis.

The 5-year relative survival rates for bladder cancer are as follows:

- 97% for carcinoma in situ of the bladder alone (abnormal cells found in the tissue lining the inside of the bladder)

- 71% for localized bladder cancer (cancer is in the bladder only)

- 39% for regional bladder cancer (cancer has spread beyond the bladder to nearby lymph nodes or organs)

- 8% for metastatic bladder cancer (cancer has spread beyond the bladder to a distant part of the body)

Learn more about statistics for bladder cancer from our Cancer Stat Facts Collection.

Understanding survival rate statistics

Because survival statistics are based on large groups of people, they cannot be used to predict exactly what will happen to you. The doctor who knows the most about your situation is in the best position to discuss these statistics and talk with you about your prognosis. It is important to note the following when reviewing survival statistics:

- No two people are entirely alike, and responses to treatment can vary greatly.

- Survival statistics use information collected from large groups of people who may have received different types of treatment.

- It takes several years to see the effect of newer and better treatments, so these effects may not be reflected in current survival statistics.

To learn more about survival statistics and to see videos of patients and their doctors exploring their feelings about prognosis, see Understanding Cancer Prognosis.

Bladder Cancer Stages

Cancer stage describes the extent of cancer in the body, such as the size of the tumor, whether it has spread, and how far it has spread from where it first formed. It's important to know the stage of bladder cancer to plan treatment.

There are several different staging systems for cancer. Bladder cancer is usually staged using the TNM staging system. Your cancer may be described by this staging system in your pathology report. Based on the TNM results, a stage is assigned to your cancer, such as stage I, stage II, stage III, or stage IV (may also be written as stage 1, stage 2, stage 3, or stage 4). When talking with you about your cancer, your doctor may describe it as one of these stages.

Learn more about Cancer Staging.

Learn about the tests and procedures doctors use to stage bladder cancer.

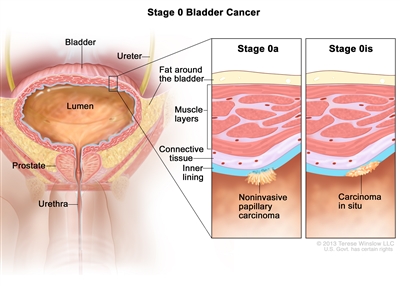

Stage 0 (noninvasive papillary carcinoma and carcinoma in situ)

Stage 0 bladder cancer (noninvasive bladder cancer). Cancer cells are found in tissue lining the inside of the bladder but have not invaded into the bladder wall. Stage 0a (also called noninvasive papillary carcinoma) may look like long, thin growths extending into the bladder lumen (the space where urine collects). Stage 0is (also called carcinoma in situ) is a flat tumor on the tissue lining the inside of the bladder.

Stage 0 refers to noninvasive bladder cancer. This means that cancer cells are found in tissue lining the inside of the bladder but have not invaded the bladder wall. Stage 0 is divided into stages 0a and 0is, depending on the type of tumor:

- Stage 0a is also called noninvasive papillary carcinoma, which may look like long, thin growths extending into the bladder lumen (the space where urine collects). Stage 0a can be low grade or high grade, depending on how abnormal the cells look under the microscope (see the section on Bladder cancer grade).

- Stage 0is is also called carcinoma in situ, which is a flat tumor on the tissue lining the inside of the bladder. Stage 0is is always high grade (see the section on Bladder cancer grade).

Learn about treatment for stage 0 bladder cancer.

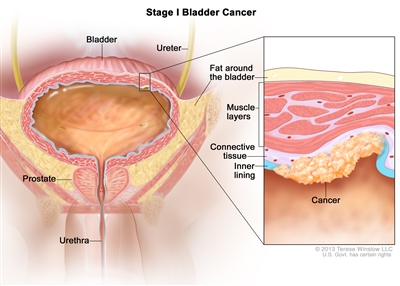

Stage I bladder cancer

Stage I is a form of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer that has spread into the connective tissue but has not reached the muscle layers of the bladder.

Stage I bladder cancer (non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer). Cancer has spread into the connective tissue but has not reached the muscle layers of the bladder.

Learn about treatment for stage I bladder cancer.

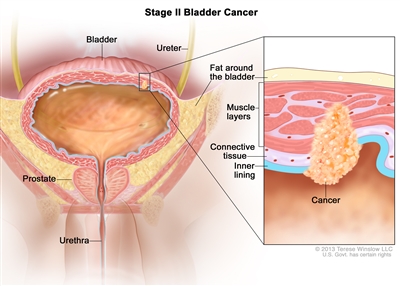

Stage II bladder cancer

Stage II may also be described as muscle-invasive bladder cancer. In stage II, cancer has spread through the connective tissue into the muscle layers of the bladder.

Stage II bladder cancer (muscle-invasive bladder cancer). Cancer has spread through the connective tissue into the muscle layers of the bladder.

Learn about treatment for stage II bladder cancer.

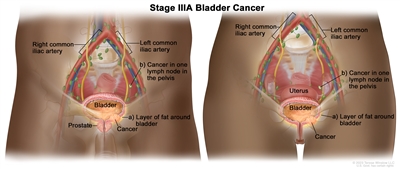

Stage III bladder cancer

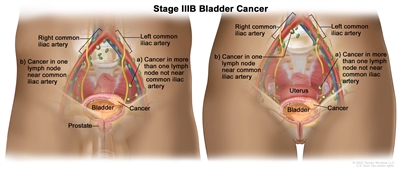

Stage III may also be described as locally advanced bladder cancer. Stage III is divided into stages IIIA and IIIB.

- In stage IIIA

- cancer has grown all the way through the bladder muscles and bladder wall into the layer of fat surrounding the bladder and may have spread to the reproductive organs (prostate, seminal vesicles, uterus, or vagina) but has not spread to lymph nodes; or

- cancer has spread to one lymph node in the pelvis that is not near the major arteries in the pelvis, called the common iliac arteries.

Stage IIIA bladder cancer. Cancer (a) has grown all the way through the bladder muscles and bladder wall into the layer of fat around the bladder and may have spread to the prostate and/or seminal vesicles in men or the uterus and/or vagina in women but has not spread to lymph nodes; or (b) has spread to one lymph node in the pelvis that is not near the common iliac arteries.

- In stage IIIB, cancer has spread to more than one lymph node in the pelvis that is not near the common iliac arteries or to at least one lymph node that is near the common iliac arteries.

Stage IIIB bladder cancer. Cancer has spread to (a) more than one lymph node in the pelvis that is not near the common iliac arteries; or (b) at least one lymph node that is near the common iliac arteries.

Learn about treatment for stage III bladder cancer.

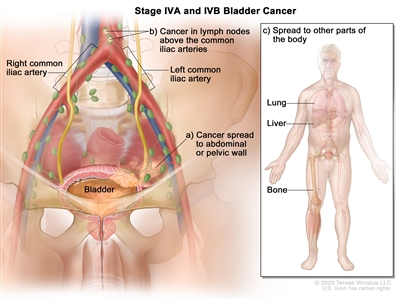

Stage IV bladder cancer

Stage IV is divided into stages IVA and IVB.

- In stage IVA

- cancer has spread to the abdominal wall or pelvic wall; or

- cancer has spread to lymph nodes that are above the major arteries in the pelvis, called the common iliac arteries.

- In stage IVB, cancer has spread to other parts of the body, such as the lung, bone, or liver.

Stage IVA and IVB bladder cancer. In stage IVA, cancer has spread to (a) the abdominal or pelvic wall; or (b) lymph nodes above the common iliac arteries. In stage IVB, cancer has spread to (c) other parts of the body, such as the lung, liver, or bone.

Stage IV bladder cancer is also called metastatic bladder cancer. Metastatic cancer happens when cancer cells travel through the lymphatic system or blood and form tumors in other parts of the body. The metastatic tumor is the same type of cancer as the primary tumor. For example, if bladder cancer spreads to the lung, the cancer cells in the lung are actually bladder cancer cells. The disease is called metastatic bladder cancer, not lung cancer. Learn more in Metastatic Cancer: When Cancer Spreads.

Learn about treatment for stage IV bladder cancer.

Bladder cancer grade

Cancer grade describes how abnormal the bladder cancer cells look under a microscope and how quickly the cancer cells are likely to grow and spread. Your doctor uses grade and other factors about your cancer, such as its stage, to form a treatment plan and in some cases, to estimate your prognosis.

- Low-grade bladder cancer cells look more like normal cells and tend to grow and spread more slowly than high-grade cancer cells.

- High-grade bladder cancer tends to grow and spread more quickly than low-grade bladder cancer. High-grade cancers usually have a worse prognosis than low-grade cancers and may need treatment right away or treatment that is more aggressive

To learn more, see Tumor Grade.

Recurrent bladder cancer

Recurrent bladder cancer is cancer that has recurred (come back) after it has been treated. Bladder cancer tends to recur after treatment, even when it is noninvasive at the time of diagnosis. Low-grade bladder cancer mainly recurs in the bladder lining. High-grade bladder cancer is more likely to have spread to the muscle layers or other parts of the body when it recurs. Tests will be done to help determine where the cancer has returned in your body, if it has spread, and how far. The type of treatment that you have for recurrent bladder cancer will depend on where it has come back.

Learn more in Recurrent Cancer: When Cancer Comes Back. Information to help you cope and talk with your health care team can be found in Coping with Bladder Cancer and the booklet When Cancer Returns.

Learn about treatment for recurrent bladder cancer.

Bladder Cancer Treatment

Different types of treatment are available for bladder cancer. You and your cancer care team will work together to decide your treatment plan, which may include more than one type of treatment. Many factors will be considered, such as the stage and grade of the cancer, your overall health, and your preferences. Your plan will include information about your cancer, the goals of treatment, your treatment options and the possible side effects, and the expected length of treatment.

It will be helpful to talk with your cancer care team before treatment begins about what to expect. Some things you'll want to learn about include what you need to do before treatment begins, how you'll feel while going through it, and what kind of help you will need. To learn more, visit Questions to Ask Your Doctor About Your Treatment. For treatment by stage, visit Treatment of Bladder Cancer by Stage.

Surgery

Surgery is the main treatment for bladder cancer. The type of surgery depends on where the cancer is located. Other treatments may be given in addition to surgery:

- Treatment given before surgery is called preoperative therapy or neoadjuvant therapy. Chemotherapy may be given before surgery to shrink the tumor and reduce the amount of tissue that needs to be removed during surgery.

- Treatment given after surgery, to lower the risk that the cancer will come back, is called adjuvant therapy. After the doctor removes all the cancer that can be seen, some patients may be given chemotherapy, radiation therapy, immunotherapy, and/or targeted therapy to kill any cancer cells that are left.

Learn more about Surgery to Treat Cancer.

The types of surgery done to treat bladder cancer are:

Transurethral resection (TUR) with fulguration

During TUR with fulguration, the doctor inserts a cystoscope (a thin lighted tube) into the bladder through the urethra. A tool with a small wire loop on the end is then used to remove the cancer or to burn the tumor away with high-energy electricity. This is known as fulguration.

Partial cystectomy

Partial cystectomy is surgery to remove part of the bladder. This may be done for patients who have a low-grade tumor that has invaded the wall of the bladder but is limited to one area of the bladder. Because only a part of the bladder is removed, patients are able to urinate normally after recovering from this surgery. This is also called segmental cystectomy.

Radical cystectomy with urinary diversion

Radical cystectomy is surgery to remove the bladder and any lymph nodes and nearby organs that contain cancer. This surgery may be done when the bladder cancer invades the muscle layers or when non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer involves a large part of the bladder:

- In men, the nearby organs that are removed are the prostate and the seminal vesicles.

- In women, the uterus, the ovaries, and part of the vagina are removed.

Sometimes, when the cancer has spread outside the bladder and can't be completely removed, surgery to remove only the bladder may be done to reduce urinary symptoms caused by the cancer.

When the bladder must be removed, the surgeon performs a procedure called urinary diversion to create another way for the body to store and pass urine. It may involve redirecting urine into the colon, using catheters to drain the bladder, or making an opening in the abdomen that connects to a bag outside the body for collecting urine. To learn more, visit the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases page on Urinary Diversion.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy uses high-energy x-rays or other types of radiation to kill cancer cells or keep them from growing. Bladder cancer is sometimes treated with external beam radiation therapy. This type of radiation therapy uses a machine outside the body to send radiation toward the area of the body with cancer. Radiation therapy may be given alone or with other types of treatment, such as chemotherapy.

Learn more about External Beam Radiation Therapy for Cancer and Radiation Therapy Side Effects.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (also called chemo) uses drugs to stop the growth of cancer cells, either by killing the cells or by stopping them from dividing. Chemotherapy may be given alone or with other types of treatment. The way the chemotherapy is given depends on the type and stage of the cancer being treated.

Systemic chemotherapy

Systemic chemotherapy for bladder cancer is when chemotherapy drugs are injected into a vein. When given this way, the drugs enter the bloodstream to reach cancer cells throughout the body. Systemic chemotherapy drugs that may be used to treat bladder cancer are:

- carboplatin

- cisplatin

- doxorubicin

- fluorouracil (5-FU)

- gemcitabine

- methotrexate

- mitomycin

- paclitaxel

- vinblastine

Combinations of these drugs may be used. Other chemotherapy drugs not listed here may also be used.

Intravesical chemotherapy

For bladder cancer, chemotherapy may be intravesical, meaning it is put into the bladder through a tube inserted into the urethra. Intravesical treatments flush the bladder with drugs that kill cancer cells that remain after surgery. This lowers the chance of the cancer coming back.

Mitomycin and gemcitabine are two chemotherapy drugs given as intravesical chemotherapy to treat bladder cancer. These drugs can also be given systemically.

To learn more about how chemotherapy works, how it is given, common side effects, and more, visit Chemotherapy to Treat Cancer and Chemotherapy and You: Support for People With Cancer.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy helps a person's immune system fight cancer. Your doctor may suggest biomarker tests to help predict your response to certain immunotherapy drugs. Learn more about Biomarker Testing for Cancer Treatment.

Systemic immunotherapy

Systemic immunotherapy drugs used to treat urothelial cancer (a type of bladder cancer) include:

- atezolizumab

- avelumab

- nivolumab

- pembrolizumab

These drugs work in more than one way to kill cancer cells. They are also considered targeted therapy because they target specific changes or substances in cancer cells (visit the section on Targeted therapy).

Intravesical immunotherapy

BCG (bacillus Calmette-Guérin), nadofaragene firadenovec-vncg, and nogapendekin alfa inbakicept-pmln are intravesical immunotherapy drugs used to treat bladder cancer. They are given in a solution that is placed directly into the bladder using a catheter (thin tube). Intravesical treatments flush the bladder with drugs that kill cancer cells that remain after surgery. This lowers the chance of the cancer coming back.

Learn more about Immunotherapy to Treat Cancer and Immunotherapy Side Effects.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy uses drugs or other substances to block the action of specific enzymes, proteins, or other molecules involved in the growth and spread of cancer cells. Your doctor may suggest biomarker tests to help predict your response to certain targeted therapy drugs. Learn more about Biomarker Testing for Cancer.

Targeted therapies used to treat bladder cancer include:

- enfortumab vedotin

- erdafitinib

- ramucirumab

- sacituzumab govitecan-hziy

Learn more about Targeted Therapy to Treat Cancer.

Clinical trials

For some people, joining a clinical trial may be an option. There are different types of clinical trials for people with cancer. For example, a treatment trial tests new treatments or new ways of using current treatments. Supportive care and palliative care trials look at ways to improve quality of life, especially for those who have side effects from cancer and its treatment.

You can use the clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials accepting participants. The search allows you to filter trials based on the type of cancer, your age, and where the trials are being done. Clinical trials supported by other organizations can be found on the ClinicalTrials.gov website.

Learn more about clinical trials, including how to find and join one, at Clinical Trials Information for Patients and Caregivers.

Follow-up care

Some of the tests that were done to diagnose or stage the cancer may be repeated. Some tests will be repeated to see how well the treatment is working. Decisions about whether to continue, change, or stop treatment may be based on the results of these tests. These tests are sometimes called follow-up tests or check-ups.

Treatment of Bladder Cancer by Stage

Bladder cancer stage and grade are important factors in deciding the best treatment for bladder cancer. Other factors, such as your preferences and overall health, are also important.

Palliative therapy aims to relieve symptoms and improve the quality of life for people with life-threatening diseases like cancer. It is helpful at all stages of cancer. Many cancer treatments can also be used as palliative therapy to enhance comfort. Learn more about Palliative Care in Cancer.

For some people, taking part in a clinical trial of new cancer drugs or treatment combinations may be an option. To learn about clinical trials, including how to find and join one, visit Clinical Trials Information for Patients and Caregivers.

Treatment of stages 0 and I bladder cancer

Stage 0 and stage I bladder cancer, also known as non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC), haven't spread to the muscle layer of the bladder. Treatment of NMIBC depends on several factors:

- the risk level of the cancer (low, intermediate, or high) for recurrence or becoming muscle-invasive

- the stage and grade of the cancer

- the size and number of tumors

The first treatment is usually a surgical procedure called transurethral resection (TUR) with fulguration to remove the tumor. Sometimes, surgery might be repeated if the first doesn't remove enough of the tumor or does not include a sample from the muscle layer. If a repeat surgery finds that the cancer has invaded the muscle layer, it will be treated as muscle-invasive bladder cancer (stage II bladder cancer or higher).

Because stage 0 and stage I bladder cancer often come back after surgery, most people receive intravesical chemotherapy with mitomycin or gemcitabine or intravesical BCG at the time of their first surgery. To help lower the risk of bladder cancer recurrence, your doctor may recommend you continue having intravesical BCG for up to 3 years, depending on the characteristics of the cancer. This is called maintenance therapy.

To learn more about the treatments below, visit Bladder Cancer Treatment.

Treatment of low-risk bladder cancer

Low-risk bladder cancer might include small, single, low-grade tumors.

Treatment typically includes TUR with fulguration and intravesical therapy given around the time of surgery, followed by surveillance. Surveillance means closely watching your condition but not giving any treatment unless the cancer returns.

Treatment of intermediate-risk bladder cancer

Intermediate-risk bladder cancer might include multiple or large, slow-growing stage 0a tumors, slow-growing stage 0a tumors that recur within 1 year, a single fast-growing stage 0a tumor, or a slow-growing stage I tumor.

Treatment typically includes TUR with fulguration, followed by intravesical therapy (BCG or chemotherapy with mitomycin or gemcitabine). Depending on the characteristics of the cancer, your doctor may recommend that you continue having intravesical BCG for up to 1 year to lower the risk of recurrence. Surveillance with regular cystoscopies (bladder inspections with a camera) and possibly additional imaging tests are used to monitor for signs of cancer recurrence or progression.

Treatment of high-risk bladder cancer

High-risk bladder cancer might include multiple or large high-grade stage 0a tumors, the presence of carcinoma in situ (stage 0is), and fast-growing stage I tumors.

Treatment typically includes TUR with fulguration, followed by intravesical BCG therapy. Sometimes, intravesical BCG is continued for up to 3 years to lower the risk of recurrence. If you have multiple tumors or carcinoma in situ, a type of high-grade stage 0 cancer, another option is surgery to remove part or all of your bladder (cystoscopy).

Treatment of very high-risk bladder cancer

Very high-risk bladder cancer might include cancer that does not respond to intravesical BCG, that recurs in the urethra, or that involves cancer cells detected in the blood or lymph system near the tumor. Very high-risk bladder cancer has a greater chance of progressing to muscle-invasive disease (stage II or higher).

If you have many tumors or carcinoma in situ (a type of high-grade stage 0 cancer), partial or complete cystectomy (surgical removal of the bladder) may be an option. If you have carcinoma in situ, cannot or choose not to have a cystectomy, and BCG did not work, other options include intravesical chemotherapy, the immunotherapy drug pembrolizumab given through a vein, or intravesical immunotherapy with nadofaragene firadenovec-vncg or nogapendekin alfa inbakicept-pmln.

Treatment of stages II and III bladder cancer

The two main treatments for stage II and stage III bladder cancer are radical cystectomy or a combination of radiation therapy and chemotherapy.

Radical cystectomy is surgery to remove the bladder and surrounding tissues and organs. Surgery to make a new way for urine to leave the body (called urinary diversion) will be done. Additional treatments may be given before or after surgery:

- Chemotherapy may be given before surgery to people who are well enough to tolerate it. Giving combination chemotherapy that includes cisplatin before surgery has been shown to help people live longer than surgery alone.

- The immunotherapy drug nivolumab may be given if the cancer has a high risk of coming back after surgery or did not respond to chemotherapy.

If you are unable or choose not to have surgery, treatment may include a combination of radiation therapy and chemotherapy, such as cisplatin and fluorouracil, given at the same time. Giving chemotherapy at the same time as radiation therapy helps the radiation therapy work better.

Partial cystectomy (removal of part of the bladder) is a less common treatment for stages II and III bladder cancer.

To learn more about these treatments, visit Bladder Cancer Treatment.

Treatment of stage IV bladder cancer

Treatment for stage IV bladder cancer depends on whether the cancer is locally advanced or metastatic. Treatment for metastatic bladder cancer is aimed at relieving symptoms and improving quality of life while also slowing the growth and spread of the cancer.

Treatment of stage IVA (locally advanced) bladder cancer may include:

- the immunotherapy drug pembrolizumab in combination with the targeted therapy drug enfortumab vedotin

- the immunotherapy drug nivolumab in combination with the chemotherapy drugs cisplatin and gemcitabine

- the chemotherapy drugs cisplatin and gemcitabine followed by the immunotherapy drug avelumab

- for people well enough to tolerate it, cisplatin-based systemic chemotherapy, such as one of the following regimens:

- dose-dense methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (MVAC)

- cisplatin, methotrexate, and vinblastine (CMV)

- pembrolizumab alone

- a cisplatin-based chemotherapy regimen followed by surgery to remove the bladder and surrounding tissues and organs (radical cystectomy) and urinary diversion or surgery alone

- radiation therapy and chemotherapy, such as cisplatin and fluorouracil, given at the same time, to help the radiation therapy work better

- urinary diversion, as palliative therapy or to prevent a blockage of urine that could cause kidney damage

- surgery to remove part or all of the bladder (cystectomy) as palliative therapy

Treatment of stage IVB (metastatic) bladder cancer may include:

- the immunotherapy drug pembrolizumab in combination with the targeted therapy drug enfortumab vedotin

- the immunotherapy drug nivolumab in combination with the chemotherapy drugs cisplatin and gemcitabine

- the chemotherapy drugs cisplatin and gemcitabine followed by the immunotherapy drug avelumab

- systemic chemotherapy, such as one of the following regimens:

- gemcitabine with either cisplatin or carboplatin

- dose-dense methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (MVAC)

- cisplatin, methotrexate, and vinblastine (CMV)

- an immunotherapy drug alone, such as avelumab, nivolumab, or pembrolizumab

- radiation therapy as palliative therapy

- urinary diversion, as palliative therapy or to prevent a blockage of urine that could damage the kidneys

- surgery to remove part or all of the bladder (cystectomy) as palliative therapy

To learn more about these treatments, visit Bladder Cancer Treatment.

Treatment of recurrent bladder cancer

Treatment of bladder cancer that has recurred (come back) depends on previous treatment and where the cancer has come back. Treatment may include:

- systemic chemotherapy, such one of the following regimens:

- gemcitabine with either cisplatin or carboplatin

- dose-dense methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (MVAC)

- cisplatin, methotrexate, and vinblastine

- an immunotherapy drug, such as avelumab, nivolumab, or pembrolizumab

- a targeted therapy drug, such as enfortumab vedotin, erdafitinib, or ramucirumab

- surgery for non-muscle-invasive or localized tumors, which may be followed by immunotherapy and chemotherapy

- radiation therapy as palliative therapy

To learn more about these treatments, visit Bladder Cancer Treatment.

Coping with Bladder Cancer

When you first learn that you have bladder cancer, you may wonder how you're going to cope with the upcoming changes in your life. One step you can take is to be informed of the physical and emotional changes that may occur and what resources are available to help you. Talking with your health care team about your concerns can give you a greater sense of control. Family and friends can also be important sources of support.

For resources on the common physical side effects of treatment for bladder cancer, see Bladder Cancer Treatment. For help with emotional side effects, see Emotions and Cancer.

For help after your cancer treatment has ended, see Cancer Survivorship and our booklet Facing Forward: Life After Cancer Treatment.

Adjusting after urostomy

For those who have a stoma and urostomy bag, getting used to them takes time. Some people need to learn how to use a catheter to empty their bladder, which is another big change. And if you have incontinence or problems controlling your bladder, it can be frustrating to deal with.

Know that you aren't alone in how you feel. Adjusting to these changes can be hard. But, over time, many people are able to do a lot of what they did before surgery. Support from family members and your health care team can help you get used to life after urostomy surgery. Ask your nurse for resources and support groups that may be helpful. Learn more about Patient's Concerns About Surgery.

Self-image and sexual problems

Body changes may affect your self-image and sex life after treatment. Some treatments for bladder cancer, including chemotherapy, radiation therapy, surgery, or certain medicines, can cause short-term or long-term problems with sex. For example, having a cystectomy may affect the nerves and make it harder for men to have an erection. Women may have pain during sex or problems with lubrication and orgasm.

It's important to discuss any issues and concerns you have about sex with your health care team before treatment. Knowing your thoughts ahead of time may help them plan your treatment.

Learn more about the sexual problems some cancer treatments can cause and ways to cope in Sexual Health Issues in Women with Cancer and Sexual Health Issues in Men with Cancer. For help communicating your feelings, see Self-Image and Sexuality.

The stress of follow-up care

It's common for bladder cancer to come back, even after successful treatment. As a result, it is important for people who have been treated for bladder cancer to visit their doctor regularly to get certain follow-up exams or tests. This can be hard for a number of reasons, such as:

- Planning and scheduling these appointments can be stressful and time-consuming.

- Waiting for test results can cause anxiety and an ongoing fear of recurrence.

- The added costs of things such as copays, medicines, and parking and transportation fees only add to the stress.

For information about how to prepare for follow-up appointments, see Follow-Up Medical Care.

For tips on how to deal with the fear of cancer coming back, see the section Coping with Fear of Recurrence on our New Normal page.

Cost of cancer treatment

Cancer is one of the most costly diseases to treat in the United States. Even if you have health insurance, you may face major financial challenges and need help dealing with the costs of bladder cancer treatment. Having cancer may also make it hard for you to work and pay your bills. The problems a person has related to the cost of treatment is known as financial toxicity. For ways to cope, see Managing Costs and Medical Information. To learn about financial toxicity and find out if you are at risk, see Financial Toxicity (Financial Distress) and Cancer Treatment.

Last Revised: 2024-09-12

If you want to know more about cancer and how it is treated, or if you wish to know about clinical trials for your type of cancer, you can call the NCI's Cancer Information Service at 1-800-422-6237, toll free. A trained information specialist can talk with you and answer your questions.